IMAGED AND IMAGINED SPAIN SEEN THROUGH PRINTS FROM JAPANESE COLLECTIONS

It’s been hot these days.

I and assistant No. 0 headed to the National Museum of Western Art in Ueno on August 11, 2023 (Friday), Mountain Day (National Holiday).

It was the first day of the three-day weekend, and despite the very hot weather, Ueno was extremely crowded, including foreign tourists.

Due to the unexpected crowd, there was a long line at the ticket office.

In Ueno, the “Ancient Mexico” Exhibition is currently being held at the Tokyo National Museum, and the “Matisse Exhibition” is being held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum. I have already introduced the Matisse exhibition in this blog.

I actually went to the “Ancient Mexico” Exhibition the other day, and I’ve already finished visiting the “David Hockney Exhibition” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, and the “Kawamoto Goro Exhibition” at the Tomo Museum, so I’m stuck in a traffic jam of topics.

However, at the request of Assistant No. 0, I would like to introduce this “Imaged and Imagined” exhibition first.

The official title of this exhibition is as follows;

SPAIN SEEN THROUGH PRINTS

FROM JAPANESE COLLECTIONS

The exhibition period of the National Museum of Western Art is from July 4th to September 3rd, 2023, but in fact it was already held from April 8th to June 11th, 2023 at the Nagasaki Prefectural Museum of Art.

「スペインのイメージ」展 入り口サイン

“IMAGED AND IMAGINED

SPAIN SEEN THROUGH PRINTS FROM JAPANESE COLLECTIONS” Sign at the Entrance

The “Foreword” reads:

*

This exhibition provides an overview of the historical development of printmaking in Spain from the beginning of the 17th century to the latter half of the 20th century. This is an unprecedented project that explores how prints contributed to the formation and dissemination of images of Spanish culture and art from about 240 works.

*

As for painters, in addition to Spanish painters such as Ribera, Goya, Fortuny, Picasso, Miró, and Dali, there are also works by painters such as Delacroix and Manet who painted “Spanish taste”.

Painters related to the World Expos are also included, so we may be able to expect to get some new findings.

Let’s take a quick look at this exhibition from an “Expo Perspective”.

Chapter 1

Chapter 1 is a section entitled “Reflecting on the Golden Age: Don Quixote and Velazquez – REFLECTING ON TRADITION “.

Works related to Don Quixote and related to Velázquez are on display.

The author, Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616), lived almost at the same time as the British Shakespeare (1564-1616). According to Wikipedia, both of them died on April 23, 1616, although there are various calendars. An interesting coincidence.

Be that as it may, in addition to prints produced in the 17th and 18th centuries, works by Honoré Daumier (1808-1879) and Salvador Dalí (1904-1989 photographs not allowed), from Figueres, Spain, are on display.

オノレ・ドーミエ 『山中のドン・キホーテ』

Honoré Daumier “Don Quixote in the Mountains”

オノレ・ドーミエ『ドン・キホーテとサンチョ・パンサ』

Honoré Daumier “Don Quixote and Sancho Panza”

フランシスコ・デ・ゴヤ『マルガリータ・デ・アウストリア騎馬像(ベラスケスに基づく)

Francisco de Goya “Margarita de Austria on Horseback, after Velázquez”

エドゥアール・マネ『スペイン王フェリペ4世(ベラスケスに基づく』

Édouard Manet “Phillip IV, King of Spain, after Velásquez”

Chapter 2

Chapter 2 is “THE ‘DISCOVERY’ OF SPAIN”.

An exhibition about people who came from abroad and “discovered” Spain.

For example, Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) and Edouard Manet (1832-1883).

Delacroix traveled to Andalusia in Spain in 1832 to see Goya’s works.

Manet traveled to Spain in 1865, stopping at the Prado Museum. Manet was a painter who was heavily influenced by the Spanish master Francisco de Goya (1746-1828).

Famous is the similarity between Goya’s “El tres de mayo de 1808 en Madrid” (The Third of May 1808, 1814) and Manet’s “The Execution of Emperor Maximilien” (1869 and others).

エドゥアール・マネ『マクシミリアンの処刑』

Édouard Manet “The Execution of Maximilian”

ゴヤ『マドリード、1808年5月3日』

Goya “El tres de mayo de 1808 en Madrid”

This exhibition also includes works by Goya, Manet, and Delacroix.

Relationship between Manet, Goya and World Expos

Speaking of Manet, he left behind various episodes relating to World Expos.

On the occasion of the 1867 Paris Universal Exposition, the second Universal Exposition to be held in Paris, Manet painted a work depicting the venue of this exposition, titled “View of the 1867 Exposition Universelle.” However, Manet’s own paintings were not exhibited at the Expo, and he set up his own solo exhibition venue, where he exhibited his works including “The Luncheon on the Grass” and “Olympia.”

エドゥアール・マネ 『1867年のパリ万国博覧会』

Édouard Manet “View of the 1867 Exposition Universelle”

In fact, Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) similarly held solo exhibitions outside the venues of the 1855 Paris Universal Exposition and the 1867 Paris Universal Exposition.

Manet’s solo exhibition was the forerunner of the Impressionist Exhibition, which was first held in 1874.

Manet died in 1883, but 14 of his posthumous works were exhibited at the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition, the fourth Universal Exposition held in Paris.

Among them were works that we are familiar with, such as “Olympia” and “The Boy Who Blows the Flute”.

Incidentally, Manet’s “Olympia” (1863), which was exhibited at the Universal Exposition, was said to be sold to the United States. It was Claude Monet (1840-1926) who left an episode that after hearing this, he started a fundraising campaign with the goal of raising 20,000 francs to prevent the outflow to a foreign country.

マネ『オランピア」

Manet “Olympia”

Also, this “Olympia” and Goya’s “La Maja Desnuda” (c.1797-1800 The Naked Maja) are very similar works, although the composition is left-right reversed.

Some say that Manet painted Olympia under the influence of Goya’s “La Maja Desnuda”.

However, “La Maja Desnuda” is a scandalous work as you can see at a glance, and there is also a story that it was kept in the basement of the Prado Museum for nearly 100 years until it was opened to the public in 1901. I’m not sure if Manet had a chance to see this work. Also, when Manet traveled to Spain was in 1865, two years after “Olympia” was completed.

By the way, as mentioned above, “Olympia” was exhibited at the 1889 Paris Exposition, and “La Maja Desnuda(The Naked Maja)” was also exhibited at a World Expo along with “La Maja Vestida” (The Clothed Maja).

It was the 1964/65 New York World’s Fair.

The venue of this Expo was full of American pop art.

The New York State Pavilion, designed by Philip Johnson (1906-2005), a representative of architectural modernism, features murals by remarkable artists such as Andy Warhol, James Rosenquist, Roy Lichtenstein, and Robert Rauschenberg and Ellsworth Kelly.

Although the Fair was full of contemporary art, there were also traditional art exhibitions.

For the first time since 1499, Michelangelo’s Pietà was taken out of the Vatican and exhibited in the Vatican Pavilion.

The realization of “the exhibition of the century” was the result of negotiations between President J.F. Kennedy and Fair Corporation President Robert Moses (1888-1981) with Pope Paul VI.

In addition, at the “Spain Pavilion“, works by Velázquez, El Greco, Picasso, and Miró were exhibited, as well as Goya’s “The Naked Maja” and “The Clothed Maja”.

ゴヤ『裸のマハ』

Goya “La Maja Desnuda”

ゴヤ『着衣のマハ』

Goya “La maja vestida”

Owen Jones and Spain

Now, let’s go back to the exhibition.

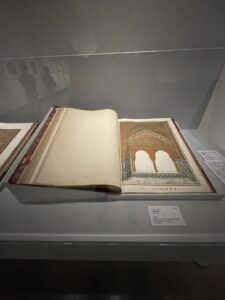

In this Chapter 2, the book “Plans, Elevations, Sections and Detail Drawings of the Alhambra” (1842-45) by Owen Jones and Jules Gouri was displayed.

オーウェン・ジョーンズ・ジュール・グーリ著『アルハンブラの平面、立面、断面、細部図集 二姉妹の間』

Owen Jones and Jules Goury “Plans Elevations, Sections, and Details of the Alhambra, Windows in the Alcove. Hall of the Two Sisters”

オーウェン・ジョーンズ・ジュール・グーリ著『アルハンブラの平面、立面、断面、細部図集 二姉妹の間』

Owen Jones and Jules Goury “Plans Elevations, Sections, and Details of the Alhambra, Windows in the Alcove. Hall of the Two Sisters”

Speaking of Owen Jones (1809-1874), he was in charge of the color design of the “Crystal Palace“, the site of the 1851 London Great Exhibition, the world’s first international exposition.

He is an architect/designer who painted the “Crystal Palace” blue, white and yellow (The Crystal Palace itself was designed by Joseph Paxton).

This was introduced in <24> “Gaudi and Sagrada Familia Exhibition”.

According to P215 of the exhibition catalog this time, Owen Jones copied the architecture and decorative design of the Alhambra with a French architect in 1834. The catalog also reads, “In 1854, he reproduced the Patio of the Lions of the Alhambra in Sydenham, London.

In 1856, he published the ‘The Grammar of Ornament,’ a collection of decorative styles from all over the world.”

This Patio of Lions in Sydenham must have been added when the Crystal Palace built in Hyde Park for the 1851 London Great Exhibition was relocated to Sydenham in 1954.

(The relocated Crystal Palace was destroyed by fire in 1936, but there still are some remains.)

When I visited Sydenham in the past, I found some remnant of it and photographed it.

シデナムのライオンのパティオ Sydenham’s Lion’s Patio, photo©️Nobuaki Kyushima

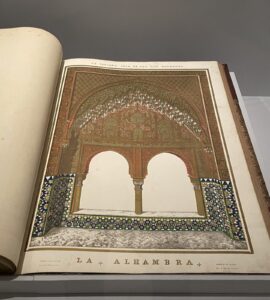

There were also several volumes of “Illustration” on display.

The “Illustration” was a French illustrated newspaper published from 1843 to 1944.

There are many illustrations related to the Expo, so it is a valuable resource.

At this exhibition, “Illustration for the review of the premiere of Bizet’s “Carmen” at the Opéra-Comique in Paris in 1875, Volume 65, No. 1672 (March 13, 1875), p. 172″ caught my eyes.

This document is displayed in a double-page spread, and on the left page there is an illustration of the first performance of “Carmen” in Paris.

『イリュストラシオン』65巻1672号

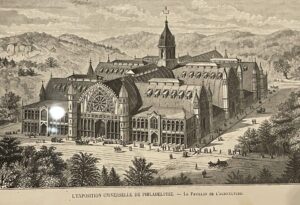

左頁が『カルメン』初演、右下にフィラデルフィア万博農業パビリオンのイラスト

“L’Illustrasion” Volume65, No.1672

“Carmen” premiere on the left page, illustration of the Philadelphia Expo Agricultural Pavilion on the lower right

However, it was the page on the right side of the spread that caught my attention.

『イリュストラシオン』65巻1672号

フィラデルフィア万博農業パビリオンのイラスト(拡大)

“L’Illustrasion” Volume65, No.1672

illustration of the Philadelphia Expo Agricultural Pavilion (Enlarged)

The caption for the illustration below is;

“L’EXPOSITION UNIVERSELLE DE PHILADELPHIE – LE PAVILON DE L’AGRICULTURE”.

In other words, this is a painting of the “Agricultural Pavilion” at the 1876 Philadelphia World’s Fair (USA).

However, this “Illustration” was dated March 13, 1875, and it was more than a year before the start of the World’s Fair (the Philadelphia World’s Fair was held from May 10 to November 10, 1876).

There are two possibilities.

For some reason, the Philadelphia World’s Fair’s “Agricultural Pavilion” was completed over a year before it opened. Alternatively, this illustration is a conceptual rendering of the “agriculture pavilion”.

Or, for some reason, the publication date of this “Illustration” is wrong.

So, I looked up the Paris premiere of Bizet’s “Carmen,” and I found out that it was “March 3, 1875.”

This means that the publication date of “Illustration” is correct, and it is highly likely that this illustration is a rendering of the completed “Agriculture Pavilion” at the Philadelphia World’s Fair.

As a writer who knows first-hand that pavilions are usually completed just before the opening of the Expo (it is not uncommon for the pavilion to be delayed for the opening), the probability that the pavilion was completed more than a year before the opening is almost nil.

I might be able to find out by reading the article about this illustration, which I can’t, because it’s not on display this time. I would like to investigate further when I have the opportunity.

However, is it an occupational disease that inevitably drawn attention to expo-related materials?

This page has absolutely nothing to do with the theme of this exhibition (“Carmen” on the left page is what they intended to exhibit and show).

Chapter 3

Chapter 3 is “BULLFIGHT, FESTIVAL OF LIFE AND DEATH“.

In this section, you can see through the exhibits that bullfighting was an important theme for Goya throughout his life, and that bullfighting was also an important motif for Manet and Picasso.

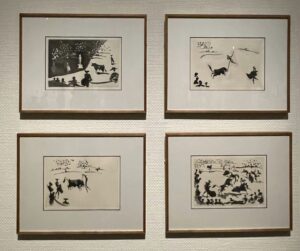

パブロ・ピカソ『闘牛技』シリーズ

Pablo Picasso “La Tauromaquia” Series

So was the American novelist Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961).

Chapter 4

Chapter 4 is “CATALONIA AND THE MODERNITY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY”.

Here, first, the print production of Mariano Fortuny (1838-1874) is introduced.

Fortuny was born in the city of Reus in Catalonia, Spain.

Speaking of Reus, he is from the same hometown as Antoni Gaudi (1852-1926).

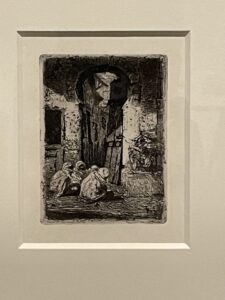

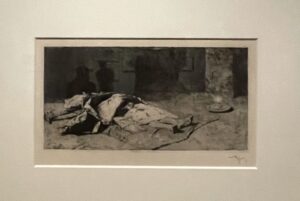

マリアーノ・フォルトゥーニ『タンジェ』

Mariano Fortuny “Tangier”

マリアーノ・フォルトゥーニ『死せるカビリア人』

Mariano Fortuny “Dead Kabyle”

Gaudi also left an episode relating to World Expos, but Fortuny is actually a painter whose work was also exhibited at the Expo.

According to the art exhibition catalog of the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition in my possession, there is the following description in the “Spain (ESPAGNE)” section.

Fortuny y de Madrazo (Mariano)

38.Portrait

In other words, one piece of work called “Potrait” was exhibited at the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition.

By the way, 38. is the work number in the Spanish section list.

It happened after the death of the painter. Just to be sure, I checked the list of exhibitors at the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition, but Fortuny’s name did not appear. It seems that his works were not exhibited at the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition.

Picasso also exhibited at the Spanish section of the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition.

According to the same document, it says;

Ruiz Picasso (Pablo)

79. Derniers moments,

This is “Last Moment” as introduced in <34> Picasso’s “Daughters of Avignon” was exhibited at the Expo!?

The exhibition then includes an exhibition on the Barcelona art movement.

This is also about the Barcelona café “Els Quatre Gats” (The Four Cats 1897-1903) and “modalnism”, which I introduced in <34>.

We know that Picasso went to “The Four Cats” from 1899 to 1900 and that he met Carreras Casagemas (1881-1901) there.

Chapter 5

Chapter 5 is “BEYOND GOYA: FINDING THE UNDERCURRENTS OF 20TH-CENTURY SPAIN ART”

Here are some artists and exhibits that you could tell at a glance that they are related to the Expo.

Picasso’s works related to World Expos

One of the artists is Picasso.

The two works, “Franco’s Dream and Lies I” and “Franco’s Dreams and Lies II” (1937), were sold as reproductions and postcards at the Spanish Republic Pavilion at the 1937 Paris Universal Exposition, where “Guernica” was unveiled.

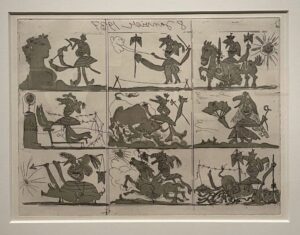

パブロ・ピカソ『フランコの夢と嘘I』

Pablo Picasso “The Dream and Lie of Franco I”

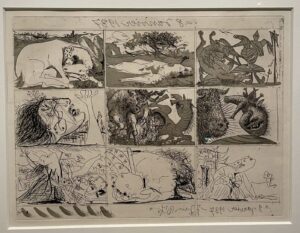

パブロ・ピカソ『フランコの夢と嘘II』

Pablo Picasso “The Dream and Lie of Franco II”

These works were exhibited at the “Barcelona, The City of Artistic Miracles” Exhibition held at Tokyo Station Gallery and other venues from 2019 to 2020, and at the “Pablo Picasso, Drawing Inspiration From the Collection of The Israel Museum Jerusalem” Exhibition held at the Panasonic Shiodome Museum in 2022.

These works are divided into 9 sections (2 sheets, so 18 sections in total), and Franco’s foolish deeds depicted in a grotesque monster are drawn from the upper right to the lower left in a cartoon style.

From the 15th frame onwards on the second sheet, there are some motifs that seems to form a part of “Guernica”.

Miró’s works related to World Expos

Another is Miló.

Miró’s “Save Spain” (AIDEZ L’ESPAGNE, 1937) is on display. (Photograph is not allowed)

This work was also exhibited in the above-mentioned “Barcelona, The City of Artistic Miracles” and “Joan Miró and Japan” Exhibition held at Bunkamura The Museum and others in 2022.

This “Save Spain” was originally planned to be used on a French one-franc stamp intended to support the government of the Spanish Republic.

After all, no stamps were issued, but it was made into a poster and sold as a limited edition at the Spanish Republic Pavilion at the 1937 Paris World Exposition, along with Picasso’s “Franco’s Dreams and Lies I & II”.

There are two versions of this poster, one with text underneath and one without.

The work on display this time is with text.

The text reads, “In today’s warfare, against the fascist camp, I admit only antiquated violence. Against the opposing camp, I admit people of immense creativity, whose creativity will give power to Spain that overwhelms the world.”

In addition to this work, Miró exhibited in the same pavilion at the Expo a huge mural called “The Reaper” depicting a Catalan peasant. (currently disappeared)

Chapter 6

And finally, Chapter 6 is ” JAPAN’S RECEPTION OF SPANISH MODERN PRINT”.

The theme here is how Spanish prints have been accepted in Japan. Works by Picasso, Miró, Tapies and others are introduced.

*

Some people may have a plain image of prints, but this exhibition was very worth seeing even just from the perspective of World Expo. In addition, the catalog contains a lot of contents, and it is worth reading.

This exhibition is worth seeing especially if you are interested in the history of the World Expo.